Let me be clear: I love a good, trashy adolescent film every so often. I make no secret my love of Crank and Crank 2: High Voltage, or of any other number of B schlock films. Even the just released trailer for Hobo With a Shotgun looks entertaining as all hell. While often regressive, politically incorrect and idiotic, these films still have a certain appeal and a sense of fun about them. Moreover, in their own odd way, they are able to tap into the undercurrents of society, even if it is doing so for purely exploitative reasons.

Let me be clear: I love a good, trashy adolescent film every so often. I make no secret my love of Crank and Crank 2: High Voltage, or of any other number of B schlock films. Even the just released trailer for Hobo With a Shotgun looks entertaining as all hell. While often regressive, politically incorrect and idiotic, these films still have a certain appeal and a sense of fun about them. Moreover, in their own odd way, they are able to tap into the undercurrents of society, even if it is doing so for purely exploitative reasons.Then, there is Heavy Metal (Potterton 1981)

It is hard to describe just how much I hate Heavy Metal, the Canadian made science-fiction/fantasy animated anthology film. It is a film that sets the bar low, and then proceeds to fail to reach even that modest height. Worse, as it fails, it takes things I love, including science fiction, pulp fiction, animation and great Canadian talent down into the gutter with it. It is as if the filmmakers were going out of their way to try and insult the viewer of the film on every conceivable level.

Heavy Metal is based on an American magazine of the same name, which itself was based upon a French magazine, from which the American version of the magazine apparently reprinted translated material. While I have never read an issue of the magazine, its reputation among genre fans is well known, both for featuring the works of noted comic artists and writers as well as for is hyper-sexual and hyper-violent storylines and images. While I cannot say the degree to which the film reflects its source material, there is no question that the filmmakers were certainly in love with the concepts of sex and violence, as these two elements are what the film solely consists of.

So, just what is the story, or stories as it is, of this anthology film? This is the first major problem with Heavy Metal, in that there is nothing in the film that can be called a story, let alone multiple stories. Yes, stuff happens on screen, but none of it is actually contained in anything resembling a narrative. I could use a famous quote from Macbeth to describe the material and the way in which it is presented, but I don’t feel like insulting Shakespeare by sheer association at this point. Technically, the so-called stories are tied together by a device called the Loc-Nar, an orb of great power which terrorises a little girl with its grizzly tales of death and destruction, which include zombies, taxi cab drivers, stoner spaceship pilots and other things that might have been interesting if anyone had actually bothered to write a script.

At this point, allow me to quote a selection from the 2004 edition of the Oxford Concise Dictionary of Literary Terms, written by Chris Baldick, about “plot“: “the pattern of events and situations in a narrative or dramatic work, as selected and arranged both to emphasis relationships - usually cause and effect- between incidents and to elicit a particular kind of interest in the reader or audience…” (195).

Now, lets breakdown one of the segments in the film. We have a set up that various random mutations are happening among the population of Earth, with a respected scientist showing up at the Pentagon to give his opinion on the matter. So far, so “ok.” In the process of doing so, however, he freaks out and begins to sexually assault a stenographer. Apparently, this has something to do with the Loc-Nar, though the how and why are unclear. Oh, and this assault is played for laughs, so, now we drift into the offensive. Then a tube breaks through the roof and sucks up the scientist and the stenographer into a spaceship, where we find out the scientist is a malfunctioning android created by another robot. Why the android was placed on Earth is never explained. Then they take off, with the stenographer still with them. Then the stenographer goes off an sleeps with a robot, while two space pilots get stoned, fly their ship, and ultimately crash land. Then the stenographer agrees to marry the robot, as long as it is a Jewish ceremony.

Now, you might believe that I have just described the basic, raw story with no finesse or actual attempt at describing the plotting that the actual filmmakers provide. You would be wrong, as the film provides no actual sense of relationship between the different parts of the “story” at any time. Even the basic idea of cause an effect isn’t present, let alone more complex forms of relationships between different elements of a given tale. And I would have been satisfied with basic cause and effect; it is not as if I went into this film expecting anything more than a collection of pulp tales. And this form of “storytelling” happens throughout the entire film, including the framing narrative, as the film follows the same pattern over and over again: sex, death, sex, gore, sex, murder, more sex followed by sex, a woman riding a dragon (surprisingly, that isn’t a sex scene), followed by more death. Oh, and the Loc-Nar exploding for some reason.

Part of the film’s narrative problems likely stem from the background of the screenwriters. The duo behind this film is Len Blum and Daniel Goldberg, of Stripes and Meatballs fame. Now, I dig Stripes and think the original Meatballs was fun though flawed, but how on Earth did anyone think that these two were the duo to write a sci-fi anthology film? Both Stripes and Meatballs were far from being tightly plotted films, with the scripts just setting up scenarios for Bill Murray and crew to be funny as possible in. While Heavy Metal does make attempts at comedy, most of the stories are played straight. Due to this, the limits of Blum and Goldberg’s skills as writers are revealed, as each segment comes off as little more than half baked sketches, waiting for an improve team to come in an fix them up.

The main blame doesn’t rest with the writers however: they didn’t hire themselves, and it wasn’t their decision to move forward with the script as it was. No, those responsibilities rest with producer Ivan Reitman as well as director Gerald Potterton. Why didn’t one of these two take a moment to read the script an realize what a piece of garbage it was? I don’t mean to insult the writers, but I have a hard time imagining that anyone would have thought producing the film was a good idea if the script is close to what ended up on screen. Potterton doesn’t really direct so much as he allows the film to spiral out of control, and Lord knows just what on Earth Reitman was up to during the making of the film.

Worse, these filmmakers took plenty of talented people down with them; Elmer Bernstein of Ghostbusters fame; comic greats Neal Adams, Howard Chaykin, and Bernie Wrightson, who worked on the film’s design; and the cast, which includes John Candy, Joe Flaherty, Harold Ramis, Eugene Levy and John Vernon. Everyone here deserved better material to work with than they received, and it is a great pity to see such talents wasted on this project. With any luck, I at would hope that they were at least able to make car payments with the cheques from this film.

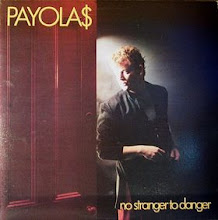

While the film has little in the way of saving graces, it would be wrong not to give credit where credit is due when it comes to the design of the film. While the finished film is poorly animated, the design work is fascinating and beautiful in its ugliness. Most notable however is the soundtrack, which is perhaps the best remember aspect of the film, as it features music from Journey, Sammy Hagar, and Devo amongst others. The music is a nice distraction from the rest of the film, and thankfully the soundtrack is available to be listened to apart from the film itself. The same however does not seem to be the case for Bernstein’s score, which only sparingly appears but is still quite wonderful when it is allowed to shine through.

I could end this review by calling the film adolescent trash designed for 13 year old boys, but I would like to give 13 year olds a little bit more credit than the filmmakers of Heavy Metal give them. Animation fans may want to check it out for curiosity’s sake, but everyone else would be better off with a Ralph Bashki film. And I not particularly a big Bashki fan.